Ten years ago, in the Autumn of 2006, I wrote an article on the Finnish School of Watchmaking, then located in Tapiola. Readers recently pointed out that the old link to that article no longer resolves. Apparently the article was taken down from its initial location on the Internet, for reasons unknown to me. In response to requests from several readers, I am now publishing this article once again on my personal blog.

by Jean-Jacques Subrenat

© 2006

(Photos by the author, unless otherwise specified)

True, Finland is better known for Nokia mobile telephones than for mechanical watches. But nowadays, in the widening circle of amateurs of horology who consult the Internet, Finnish references tend to crop up much more frequently. One Finn has even made it into the small circle of world-class watchmakers: Kari Voutilainen, who set up shop in Môtiers (Switzerland) in 2002, is already a reference, and his name is uttered in the same breath as those of a handful of other respected masters. And another up-and-coming Finnish craftsman, Stepan Sarpaneva, who set up his atelier in Helsinki in 2003, is beginning to attract attention as much for his technical innovation as for his bold styling.

Like many amateurs of horology, I wondered how a country like Finland, not known for producing any significant number of watches, has managed to educate and train generations of high-level watchmakers, and why many happen to be active in some of the most renowned ateliers. At the moment, 25 to 30 Finns are working for such companies as Audemars-Piguet, Blancpain, Breguet, Christophe Claret, Omega, Rolex, or Ulysse-Nardin, and it is noteworthy that many of them are involved in the execution and assembly of complications and limited series. This paradox, I thought, was worth looking into.

Helsinki in the summer: a gathering of wooden boats on the island of Suomenlinna

Arriving in Tapiola by bus and having a stroll before my appointment at 9:30 a.m., a day in late August 2006, I was struck by the contrast between the rambling public park of Tapiola, and the modest proportions of the building in which the school has been housed since 1959. After all, the school was established 62 years ago, and has been here in Tapiola for the past 47 years, so I expected something a bit grander, perhaps an ornamental staircase…

The public park in Tapiola and, behind the trees, the Finnish School of Watchmaking

The Finnish School of Watchmaking in Tapiola

The Director (“Rehtori” in Finnish), Ms Tiina Viitanen, who has held this position since 2002, greeted me in fluent French, and took me into the building to meet some interesting people.

Ms Tiina Viitanen, Director of the Watchmaking School in Tapiola.

The brass plate simply states “Watchmaker, the professional of time”

In the meeting room, morning coffee was served with a choice of salmon pie and berry cakes so typical of Finnish hospitality. Here were the people directly responsible for ensuring the quality of education and training in this school in Tapiola. At the end of the table, on the left-hand side, a gentleman had an aura of experience and wisdom about him, Jorma Tuominen, a grand old man of Finnish watchmaking. Tom Roos, the Chairman of the Trust Fund for Promoting Watchmaking Skills (“Kellosepäntaidon edistämissäätiö” in Finnish), sat on the right, next to Ms. Viitanen.

The faculty (in white blouses) and management of the School of Watchmaking.

From left to right: Eneli Pöysä, Reijo Rautakoski, Markku Huhtala, Jorma Tuominen,

Juha Kauppinen, Antti Miettinen, Jouni Pöllänen, Tom Roos, Tiina Viitanen

The meeting, kindly prepared by Ms. Viitanen and her staff, was a unique opportunity to learn more about this vocational school, before going to meet the students and their teachers in the workshop-classrooms.

The School of Watchmaking was first established in 1944 in Lahti,100 km North of Helsinki. The requirement in those days was not creativity, but simply good workmanship for the repair and unkeep of clocks and watches, in a country which did not have many wealthy people, and where even modest timepieces were handed down as family heirlooms (for instance, my friend Turo had two grand-aunts who, between the two World Wars, had each inherited something of value: one received a small island in the Gulf of Helsinki, the other a pocket watch…). In 1959 the School was transferred to Tapiola, a Western suburb of Helsinki, not far from the area where Nokia set up its corporate headquarters in the 1990s.

The curriculum of the school has evolved over the years to keep up with technical developments in the industry, but the initial programme was inspired by that of the watchmaking school in Glasshütte, and today the teachers still view this ancestry with pride.

3rd-year students. On the wall, an old industrial drawing from Glasshütte

Today, the link between Tapiola and Glasshütte remains strong, and contacts with the in-house school of Lange & Söhne are lively. The disciplined education established long ago in Glasshütte is carried on here in Tapiola, where all future watchmakers start with the modest but essential experience of crafting their own tools, then graduating progressively from large to smaller clocks, and only later to wristwatches and finally to complications.

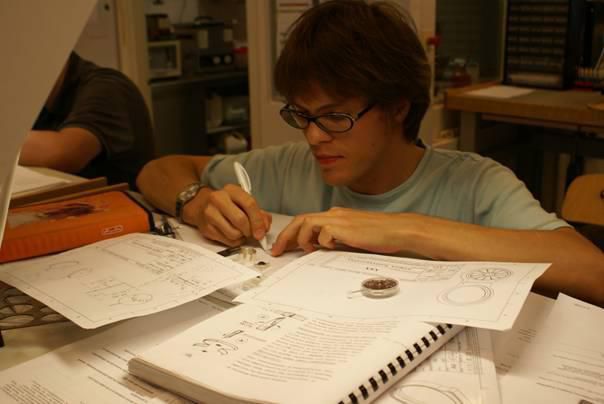

1st-year student Kimi Miettinen, aged 16, making his very first watchmaker’s tool, a scraper. During the first months at the bench, it is advisable to protect one’s fingers from wear and tear

How were students chosen, I asked the teachers and administrators assembled in the meeting room? For the term 2006-2007 which started in mid-August, the school received 125 requests from candidates, of which 60 turned up for the entrance exams, and out of this number the school finally recruited 24 new students. Tests included a psychological profile to determine motivation and character, a series of technical subjects, but also practical ability to detect problems and solve them. The teachers I met told me the general standard of new students was invariably high, which is not surprising when you consider that, for the past four years, Finland has been at the top of world ratings for the quality of secondary (pre-university) education (PISA ranking established by OECD).

Three features of the school seemed to me quite striking. The first is that a fairly high proportion of students have chosen watchmaking after having worked in other fields (during my visit, I met a computer engineer, an electrician, a nursery-school teacher, a theologian, a translator…). The second is that time allocation is one third theoretical study and two thirds practical watchmaking. The third is that, as soon as students have acquired the necessary skills, they actually repair clocks and watches for real-life clients, and if a spare part is not available, you just have to make it yourself, whether that happens to be a cog, a chime-striking mechanism, or a complete escapement. This gives each and every student a very real sense of responsibility, as he or she repairs not an abstract object, but a venerable mantlepiece clock belonging to old Mrs. Koskinen, a pocket-watch which Mr. Vuorinen took the trouble to bring to the School himself, or a wrist-watch of the 1960s which was sent from Lapland by Ms. Rantanen…

Markku Tuomi, an established professional translator, has an interest in the history

of the measurement of time, and in timepieces by old masters. He is now a

2nd-year student in Tapiola

Jouni Pöllänen and some of his 2nd year students

3rd year student Teemu von Boehm planning the pocket-watch he will entirely execute and present for his final exams

A visitor can readily sense that the atmosphere in the classrooms is relaxed, professionnal, project-driven. All of the teachers are former students of this school, and most of them have gone through one or several WOSTEP courses in Switzerland. Since taking up her position as Director, Ms. Viitanen has changed the teaching methods so that, over a period of several years, each professor gets the opportunity to teach at all levels, both theory and practice.

I was lucky that former professor Jorma Tuominen was at the school on the day of my visit. After the breakfast meeting, I had a quiet chat with him, he speaking in Finnish (which I understand a bit) and me in French or English with Ms. Viitanen kindly interpreting. After his own training in Lahti, he had gone to work for Patek Philippe in the late 1950s, and upon returning to Finland, began a long career teaching watchmaking, from 1966 to 1995. Now aged 76, he still goes regularly to the Tapiola school where his advice is eagerly sought. His hands are as steady as those of a brain surgeon, and just recently, he was still teaching students to make and adjust hairsprings!

Jorma Tuominen, an acclaimed yet modest “grande figure” of Finnish watchmaking

During our conversation, I asked Mr. Tuominen if watchmaking in Finland had changed much in the past half century. Yes, he replied, in the 1950s and 1960s his students spent as much as 46 to 50 hours a week in school, whereas nowadays they spend 32 hours (plus 8 hours for those who want to have extra training hours, and these additional classes are invariably full!). In the early years, the standard of living was not high in Finland, so that students were mainly dealing with repairing and making parts for simple and widespread movements, and rarely anything complicated in wristwatches. Today, so many more models are in circulation. An affluent society is providing many more potential watch-owners and collectors, so that creativity has come into its own, and students are encouraged in this direction.

I asked Mr. Tuominen about his former students. He chose to speak of Kari Voutilainen, whom he trained personally during the 3 years at the School in Tapiola: “Voutilainen showed great potential, was conscientious, thorough, and by the time he left the School he had acquired a wide range of abilities, which you usually meet in more senior, more experienced watchmakers”. The former teacher is pleased that this student has proven to be creative, and that the quality of his works is acclaimed beyond the borders of Finland.

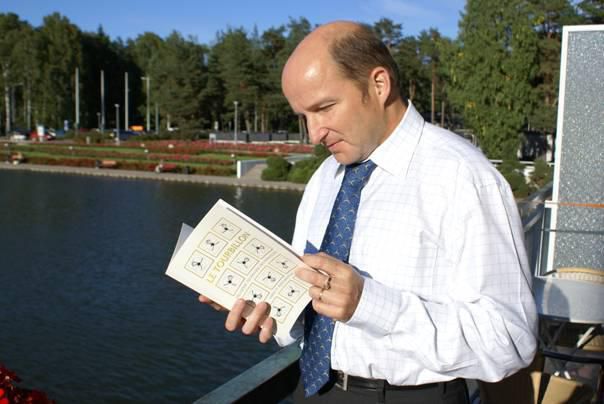

Kari Voutilainen recently in Tapiola, with the catalogue of an exhibition on tourbillons

(1996 in Switzerland), in which his own tourbillon pocket-watch was selected as

a contemporary example, alongside historic timepieces by A.-L. Breguet,

Albert Pellaton and other great masters

I asked Mr. Tuominen why he thought there were quite a few of his fellow-countrymen working for well-known Swiss watchmakers: did Finns have some magic ability, or could their success be attributed to the education they received in Tapiola? In Mr. Tuominen’s evaluation, the strength of Finnish craftsmanship lies in the successful balance which is achieved between theory and practice during the 3 years’ tuition in Tapiola, their willingness to learn, and the fact that watchmaking is taught in a very demanding way, but without stress. The retired teacher, whom students, teachers and the profession in this country all consider as a “grande figure” of contemporary Finnish watchmaking, added another remark: in the heyday of the digital watch which almost led to the demise of the mechanical watch industry (roughly from the 1960s to the 1980s), hardly anyone in Switzerland was attracted by the painstaking training to become a watchmaker, and this led to a “generation gap”. Today, the effects of this “gap” are felt throughout the industry, which is clamoring for competent craftsmen in greater numbers. In this context, the pursuit of excellent teaching in Tapiola, even in the fallow years of mechanical watchmaking, allowed Finns to remain competitive, so that today they fill an appreciable number of positions in the Swiss industry.

In the weeks before I met Jorma Tuominen, I went to meet two of today’s prominent Finnish watchmakers, and asked what their schooling in Tapiola had brought to them, and why there were quite a few Finns working in some of the well-known watch companies in Switzerland.

Kari Voutilainen and I had agreed to meet at the Museum of Horology in Tapiola, a stone’s throw from the Finnish School of Watchmaking, his alma mater. That day in late August 2006, he had personally set up 3 of his timepieces in the temporary exhibition celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Finnish Watchmakers’ Association, which had just been opened to representatives of the media (including a television team) for a preview. When I arrived, Kari took me into the quiet exhibition space, turned on the lights and projectors, and invited me to look at the exhibits: old timepieces amorously restored by members of an association of amateur watchmakers, projects designed and executed by young Finnish professional watchmakers, end-of-school projects designed and executed by students of the School of Watchmaking, one showcase for Stepan Sarpaneva, one (the most sober, but also the most outstanding) with only 3 watches by Kari Voutilainen, and one for Suunto the company which makes wrist computers and electronic watches.

I asked Kari about his experience at the Finnish School of Watchmaking.

At the Museum of Horology in Tapiola, Voutilainen showing his tourbillon pocket-watch, made after working hours (1992-96), and which attracted praise from his peers

Kari Voutilainen told me about his childhood and youth in Lapland. Even as a young boy, he says, he knew he would one day choose a profession in which he could use his hands, and which would allow him to work as an independent craftsman. A friend of the family had a small shop in Kemi, selling and repairing clocks and watches, and this attracted young Kari. Later, he read a brochure about the watchmaking school in Tapiola, where he sat for the entrance exams at the age of 19. He has a very vivid recollection of his admission to the school: right from day one, he immediately felt he had entered his element, and he knew then and there that he would never have any problem with motivation. I asked him about teaching methods: “Starting by having to make one’s own tools, dismantling, assembling and repairing first large clocks, then smaller clocks, then wristwatches, all this amounted to such an obviously wise way of training young people. It’s surprising that Tapiola is one of the only watchmaking schools in the world, if not the only one, where this basic principle is still scrupulously respected”. Kari also points out that during the whole of his 3 years in Tapiola, he had the same main teacher, Jorma Tuominen. What kind of teacher was he, I asked? “His most precious gift to youngsters like me, apart from the fact that he was an outstanding watchmaker, was that he knew how to push us always one step further than we thought we could go. Even when we had done what we considered a pretty good job, the most he would utter was “hmm, not bad; let’s see if there’s a way you could improve that”, but always in an attentive way, with patient kindness, so that discipline and self-confidence were not at odds with one another in the budding watchmaker.

Kari Voutilainen is well qualified to give an opinion on his former school in Tapiola: after all, he not only attended 2 WOSTEP courses (first in 1988, followed in 1989 by the one on complicated watches), but also was a replacement teacher at his former school in Tapiola (1988-89), and later taught at WOSTEP for 4 years (1999-2002). Looking back at his student years in Tapiola, he remembers “the very special atmosphere, the fact that we were made to feel responsible at a very early stage, knowing that no problem was beyond the understanding of our teachers, and having acquired self-confidence thanks to our very thorough training”. Discovering his patience and obvious talent in sharing his enthusiasm and experience, I asked Kari if he could have dedicated his life to teaching? “Well, I did spend quite a few years teaching, and this was satisfying in its own way because of the close relationship you establish with the students, and because teaching forces you to clarify your own experience and thinking. But after a while, I realized I no longer had enough time to carry forward my own creative work, so I left teaching in 2002 to set up my own little atelier”.

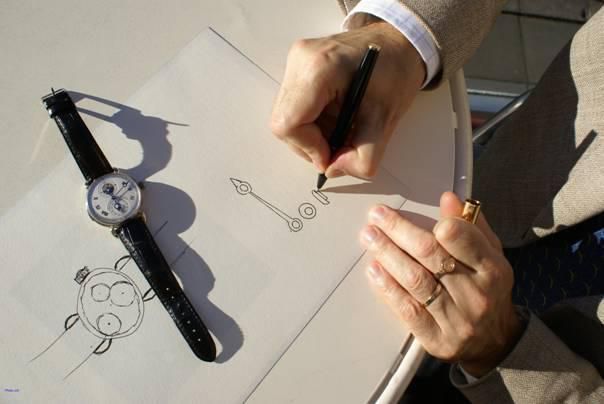

During our conversation, I sensed that creating and teaching were not different worlds for Kari Voutilainen. I asked him if he would show me, with pen and paper, how he had gone about designing one of the watches which attracted world attention, his Chronographe. He was kind enough to oblige, and I felt like a privileged student, as he began to sketch and explain. He drew the round case, the three sub-dials, and gradually competed the drawing. His pen went over and over the rounded lugs, the winding crown with its sapphire cabochon, the design and finishing of the hands which are part of his personal style. Yes, I thought to myself, someone capable not only of calculating and designing an oustanding movement, but who can also execute every part of it to the highest known standards in the world, someone who can endow the humble hands of a wrist-watch with such elegance, who can fashion the lugs of a watch casing in such a distinctive fashion, surely such a singular craftsman had made the most of his education at the school in Tapiola.

Kari Voutilainen showing the way he designed his “Chronographe”, and drawing in

detail the hands of that famous watch. His own “Masterpiece 7”, poised on the table,

casts the shadow of a dragon…

A couple of weeks before meeting Kari Voutilainen, I had gone to see another Finnish watchmaker who had likewise attended the School of Watchmaking in Tapiola. Stepan Sarpaneva worked in Switzerland for more than ten years (Parmigiani, Vianney Halter, Christophe Claret…) and established his own watchmaking atelier in Helsinki in 2003. He had this to say: “For sure, the very thorough education in watchmaking in Tapiola is one of the main reasons why my fellow-countrymen and colleagues are appreciated. There’s also our attitude towards watchmaking: to enter such a demanding profession, we Finns would not even contemplate jumping over any of the modest yet essential steps towards achieving true technical expertise. Because Tapiola gave us such a solid background, we were able to fully benefit from the valuable experience we gained later when working abroad. This combination provided us with a good system of values and references: we are steady, reliable, and very attentive to overall excellence. And a strong interest in innovation and technology probably helps us keep up with interesting developments”. As for his former teachers, Stepan considers that the good blend of discipline, competence and openness they displayed was a very reassuring factor for aspiring watchmakers. It is interesting to note that in a separate interview, Kari Voutilainen expressed similar opinions, adding that it is the quiet dedication of teachers like Jorma Tuominen and Hannu Ruokola, and the fact that they knew inside out anything they had to teach, that gave the young generation a sense of respect for excellent craftsmanship, and the urge to follow not only their teaching, but also their example.

Stepan Sarpaneva, a former student of the Finnish School of Watchmaking in Tapiola, established “Sarpaneva Watches” in Helsinki in 2003

But let’s come back to Tapiola. How does the School envisage its future, I wondered? I first had a separate conversation on this with Tom Roos, Chairman of the Trust Fund for Promoting Watchmaking Skills (“Kellosepäntaidon edistämissäätiö” in Finnish), which supports the School financially.

Tom Roos, Chairman of the Trust Fund for Promoting Watchmaking Skills, which supports the Finnish School of Watchmaking

T. Roos underlined that the school in Tapiola is a private establishment, supported by the Trust Fund, and although it receives a government subsidy, it enjoys greater liberty in governing itself and in establishing its educational programme than a State-run school. The Board is composed mostly of professionals of watchmaking, and as a result the curriculum, the teaching methods, the attention paid to the evolving requirements of business, largely reflect the concerns and wishes of the industry. Because the school is well attuned to the requirements of end-users, there is practically no unemployment in this business sector in Finland. The financial situation is sound as the School is not indebted, nor operating at a loss, but there is a sense among faculty and management that a larger budget would create better working conditions, allowing the school to become more attractive for the next generation.

Another important feature is that the School offers a combined curriculum in watchmaking and micro-mechanics. In case of a severe downturn in business prospects in one field, the slack could be taken up, at least in part, by the other. From a Finnish perspective, as Ms. Viitanen pointed out, micro-mechanics is of particular importance in terms of potential employment, and people with that qualification are already in high demand.

The premises used by the School since it moved to Tapiola in 1959 have become too small. Whereas it began with 3 classes of 13 students each, the School now has 6 classes of 13. The plan to move to a new location, which has been under discussion for about 3 years now, will soon be implemented: in the Spring or early Summer of 2007, the School will move to neighbouring Leppavaara, where the former public library is undergoing a major overhaul in order to accommodate its future tenants (both Leppavaara and Tapiola are townships administered by the municipality of Espoo). Looking at the future, Tom Roos considers that in the medium term an additional effort may become necessary to attract good students to the School, among other reasons because new generations are even more than before attracted to business management, finance or electronics. In this sense, moving to modern, well-endowed and confortable premises should help attract the best students. As for the prospect of future employment, T. Roos considers that several factors should keep the outlook favourable: the combination of micro-mechanics and watchmaking opens up wider job opportunities; faculty, management and students all engage very much in international exchanges, so that the school keeps abreast of trends and innovations worldwide; and the scarcity of vocational schools offering combined watchmaking and micro-mechanics should keep the Finnish school in business for many years to come.

I inquired about the international relations of the School. Tiina Viitanen pointed out the existence of a strong Northern European link, with a 2-week exchange programme for students every year between September and October. In the past, Germany was a prime source of inspiration for teaching, and the Glasshütte tradition has been pursued with a similar school in Villingen-Schwenningen.

Kari Voutilainen, who desings and crafts outstanding watches in Môtiers (Switzerland),

wearing the graduation ring of the Finnish School of Watchmaking, which depicts

an escapement wheel and, in its centre, an hourglass

As I put away the note-book and the camera in my backpack, and prepare to leave, I look around. Yes, the present premises of the Finnish School of Watchmaking in Tapiola show their age, and it’s no doubt time to move to the modern amenities offered in Leppavaara. But, as I catch the bus back to Helsinki, it seems obvious to me that the important elements are solidly built into the tradition of the School: the vitality and thoroughness of the teaching, the atmosphere of trust between teachers and students, the blend between discipline and the liberty to create. In this context, I’m sure the attraction of the School of Watchmaking will grow with the rising fame of former students such as Kari Voutilainen, whom today’s greatest Swiss watchmakers consider their equal: a true “maître horloger”, trained in Tapiola./.

/image%2F0000001%2F20170514%2Fob_f9fccb_dsc00014-jpg-2-copie.jpg)